Architects for summers: 5 masters to pack for your lazy days

Some pack romance novels. Others go for thrillers or crossword puzzles. We packed five architects. No technical manuals, we promise. Just a bit of forma mentis to slip in between your beach towel and SPF 50. Zaha Hadid, Frank Lloyd Wright, Renzo Piano, Tadao Ando and Bjarke Ingels: they may not sound like a summer band, but in their own way, each of them has reimagined how we live and shape space. After all, isn’t summer a kind of life sketch with fewer constraints and more natural light?

Zaha Hadid: getting it wrong, beautifully

No ruler. No symmetry. Just curves, fluid tensions, and a touch of creative chaos. Zaha Hadid taught us that you can be radical and glamorous, off-balance and monumental. Her buildings seem to surf the asphalt, driven by a visionary stubbornness that bent concrete, software and prejudice alike. Here’s your takeaway: imperfection can be a signature. And every sharp corner might be hiding a brilliant idea.

Frank Lloyd Wright: making room for nature

The waterfall house, the floor that “follows” the landscape, the vanishing walls. Wright didn’t build on nature, but with it. He designed the first truly modern home and let it breathe in the woods. Because the environment isn’t a backdrop. It’s a co-star. Ignore it, and sooner or later it’ll come knocking, even on your energy bill.

Renzo Piano: balance, modularity and patience

The man who put wheels on museums (Pompidou) and lightness into concrete (Centro Botín). Renzo Piano is the master of the invisible detail, of technology that hides in plain sight, of architecture as poetic engineering. As he shows us, the perfect design is the one that looks effortless, but took twenty-five prototypes to get right.

Tadao Ando: silence in reinforced concrete

Former boxer, self-taught architect, minimalist poet. Tadao Ando sculpts light more than he builds structures. He gave concrete a sense of spirituality, creating temples of emptiness and calm. Let’s not beat around the bush: sometimes, subtracting is the only way to bring out the essence. (And yes, that goes for silencing your notifications too.)

Bjarke Ingels: the LEGO-loving starchitect

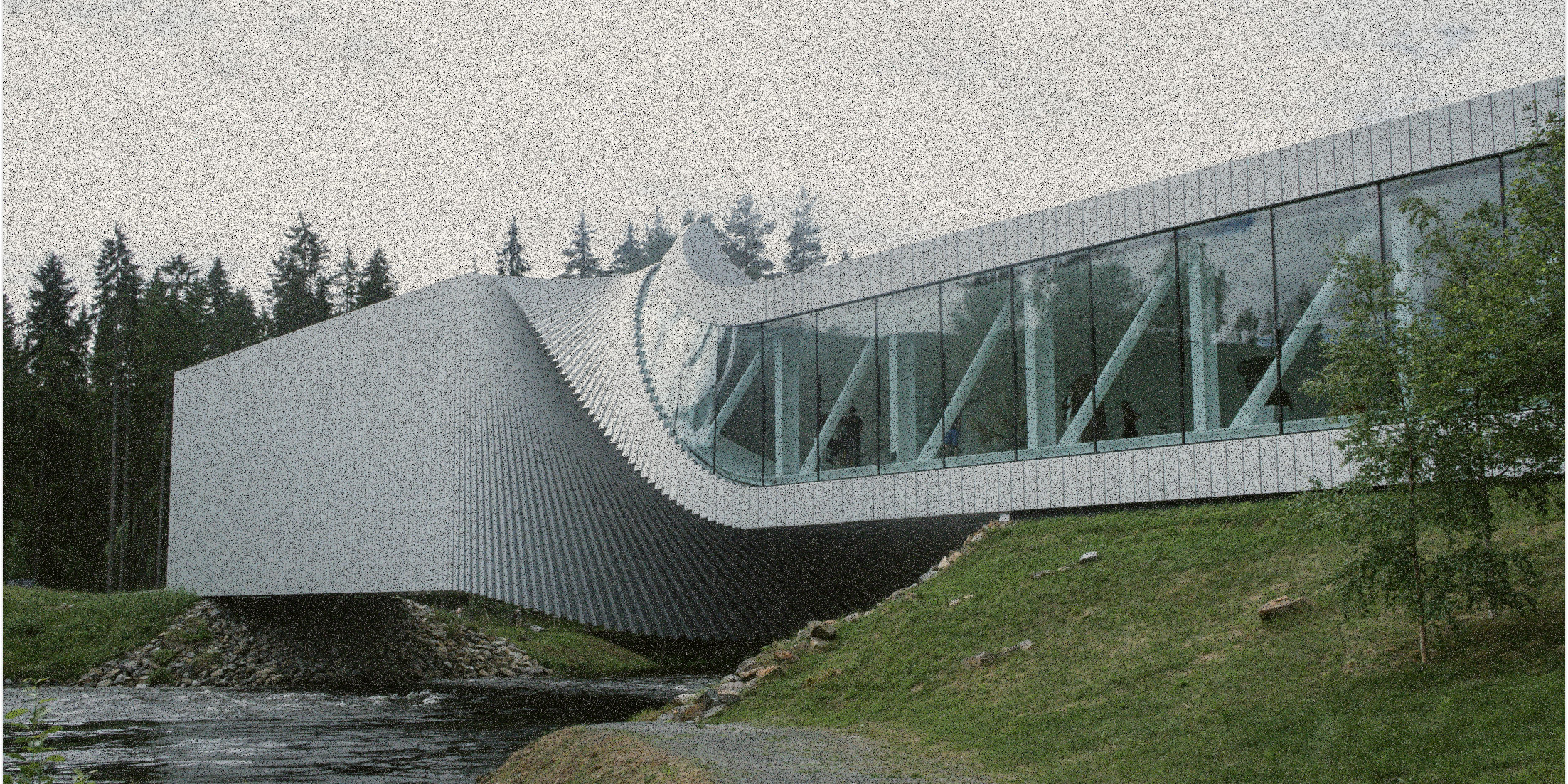

An artificial mountain, a ski slope on a residential block, a panda-shaped masterplan, nothing’s too far-fetched for BIG (Bjarke Ingels Group). Ingels blends ecology, humour and marketing without blinking. He knows the future is built with leisure in mind. After all, if sustainability isn’t fun, it won’t stick. And a touch of humour is often the secret ingredient in any great design.

In the end, we all know: architecture is everywhere. Even under your beach umbrella, somewhere between a granita, a sandcastle and a sideways thought. And these five masters remind us that design isn’t (only) about building. It’s about choosing how we want to live, even in August.

What your Office Does When Everyone’s on Holiday

The shocking news? No, it doesn’t launch into guided meditation sessions. But it might just teach you something.

I hear the echo. The fridge is empty. The access badge no longer beeps. The coffee machine has stopped making those familiar noises. But I’m still here. Watching the sunlight sketch geometries across empty desks. Keeping an eye on the plants, real and fake. Wondering: why was I designed for full capacity, when no one thought about the empty times?

Measuring absence to design for presence

Every August, the same scene unfolds: empty offices, abandoned meeting rooms, square metres left unused. But hold on, this isn’t a glitch, it’s an opportunity. Periods of underuse are a key indicator, and if you know where to look, they reveal exactly how your space (doesn’t) work.

Who’s using what? When? For how long? And most importantly: why do some areas stay deserted even when the office is full? Monitoring space usage — flows, peaks, dwell times, activity mapping — lets you move from “it feels like” to “we know for sure”. And it’s often the quiet of the off-season that gives you the clearest view.

In these cases, data analysis isn’t about justifying a choice already made, it’s about guiding the next one. It helps you see where to invest, where to reallocate resources, where less space is enough (and where better space is needed). Because office ROI isn’t just about how many people work there, it’s about how much value the space can generate even when no one’s around.

A space that works even when it isn’t needed

A good design listens. It embraces fluctuations, anticipates absence, creates value even in silence. That’s where adaptive design comes into play: movable furniture, reconfigurable environments. Designing with downtime in mind — those moments when space slows down and shifts — is a form of operational intelligence. It’s the most practical way to make sure your office stays truly alive.

A well-designed office isn’t just a container for people. It’s an elastic system, able to respond in every mode: peak, average, low. And even low-low, like in August. It’s exactly when everything stops that a space shows its true nature. If it stays flexible, welcoming, and coherent — even with just five people inside (as if they were beta testers) — then you know you’ve made it work. And if you’re still wondering, Altis is here for you. Write to us at [email protected]

Out of office: tips for a clean digital detox

You said, “I’m off on holiday.” You set your out-of-office. You downloaded three books onto your Kindle. And yet, there you are: one eye on the sunset, the other on your notifications. If that sounds familiar, you’re not alone. It happens to many of us. Because it’s not just about switching off your phone, it’s about powering down an entire culture. We explored this summer paradox with Nicoletta Brancaccio, Architect and Head of Research at Altis, who helped us understand why disconnecting is so difficult, and how both mental and physical space can make it easier.

Spoiler: we don’t have magic potions or moral lectures. Just a closer look at the patterns that keep us glued to the screen… and how to spot them when the opportunity arises.

The brain doesn’t like stopping

Switching off takes effort, it goes against the way we’re wired. Our brains crave constant stimulation and notifications: each one a micro-reward, a hit of instant dopamine. Turning everything off is like cutting off the oxygen supply to a deeply ingrained habit. But there’s more. As Nicoletta points out: “Disconnecting doesn’t mean doing nothing. It means creating the conditions to process something new. It’s an active pause, not a passive one.” In other words, detox isn’t about halting, it’s about shifting gears. It’s when lateral thinking kicks in: creative solutions that emerge when we break free from our usual patterns. No wonder the best ideas come during a walk or under a beach umbrella, it’s all about timing.

When disruption is a good thing

Space can help us switch off, but it can also make it harder. The truth, says Nicoletta, is that “we don’t need to turn off the Wi-Fi. We need to turn on curiosity. And sometimes, to do that, you need to disrupt. Not by creating discomfort, but by breaking the pattern, surprising people.” That’s when a gap opens up: a new kind of attention is born, an unexpected emotion emerges. “Disruption isn’t a glitch, it’s a generative lever.” Spaces that are too symmetrical, monotonous, or predictable end up dulling us. Changing light, non-orthogonal geometry, or a corridor that splits unexpectedly: these are the elements that can reawaken us. But designing them takes intention: fewer Instagrammable furnishings, more multisensory languages that gently nudge our attention.

Emptiness isn’t wasted time, it’s fertile ground

“To truly regenerate, you need to cross a threshold. And that threshold is made of boredom, silence, emptiness.” Nicoletta reminds us of something counterintuitive: idle moments are essential. They’re a transitional space where the brain stops reacting and starts reorganising — thoughts, memories, emotions. A time that doesn’t produce immediately, but prepares the ground. The problem? No one teaches us this. For it to happen, we need to slow down, but more importantly, we need to feel allowed to. And that’s where the trap lies: we live in a culture of performance. Even our downtime is hyper-planned: over-planned holidays, mindfulness wake-up calls, and to-do lists full of things to tick off. Emptiness is the time of incubation. But to benefit from it, we have to welcome it.

We’re not suggesting you throw your smartphone out the window (tempting as that may be). You don’t need to disappear, you just need to know where to begin again. Detox isn’t just a break from Wi-Fi or a challenge to see who can last longest without opening WhatsApp. It’s a “form of applied clarity”: one that’s physical and relational. “Every action starts with intention. Even empathy is an intentional activation.” That’s why we need to design spaces that don’t just host us, they listen to us. Because in the end, we are natural beings. And as Nicoletta reminds us: “Nature is the highest form of intelligent imperfection.” Maybe it’s time to take our cue from her. And perhaps start small: like finishing this article, and going out to enjoy that sunset, for real.

In Praise of Emptiness

We live in a world of full. Full optional, full time, fully booked. But is this really an achievement or a subtle kind of condemnation? In our collective obsession with filling every centimetre, physical or mental, we’ve forgotten what it means to leave space. Yet emptiness isn’t a design flaw: it’s a conscious choice.

In architecture, emptiness is the pause that allows the eye to move, the body to breathe, and the mind to think. Outside of architecture, emptiness is the condition of possibility for anything to exist. Think of music: without rests and silences, there would be no melodies, only indistinct cacophonies.

And yes, we know: this isn’t the classic article you skim between one meeting and the next. This is more of an invitation. In the next few paragraphs, we’ll walk together through this undefined space with four different insights – from art to philosophy, music to the sense of care – to discover that emptiness, perhaps, is fuller than we imagine. As Isabella Ducoli, Head of Design at Altis, says: “In architecture, emptiness is not absence: it’s possibility. It’s the only space you don’t have to fill, but that asks to be traversed.”

1. Rachel Whiteread: sculpting the invisible

Rachel Whiteread, a British artist, has quite literally transformed emptiness into matter. Her works are casts of empty spaces: she fills with resin or concrete the places that usually remain invisible – the inside of a house, a bathtub, a bookshelf – giving us back their negative space as sculpture. As if to say that emptiness is a reversed fullness. A fullness that speaks of who was there, what it contained, of entire lives moving within those volumes. Because without emptiness, no space would ever truly be habitable: we couldn’t cross it, live in it, or act within it.

2. Gordon Matta-Clark: cutting to reveal

Then there is Gordon Matta-Clark, the American architect and artist of the Seventies, famous for his radical cuts into abandoned buildings. He would slice through walls to reveal their interior, creating huge architectural wounds that became new spaces of light and experience. For Matta-Clark, emptiness was a political gesture: it revealed what was inside, laying bare the essence of things, and of ourselves. As Isabella Ducoli comments: “Emptiness is an active field. It’s what happens when you remove the superfluous and leave only space for what matters.”

3. John Cage: the sound of silence

But you don’t need to get your hands dirty with concrete or wield a circular saw to understand emptiness. John Cage, an American composer, taught us that silence is also full of sound. In 1952 he composed 4’33”, a piece where the performer plays no notes. Four minutes and thirty-three seconds of apparent silence in which, in reality, you hear everything: coughing, chairs creaking, rain on the roof, the breathing of those in the room. Cage reminds us that emptiness is always full of something, you just need to know how to listen.

4. The Altis perspective: emptiness as care

If everything around us is oversaturated, emptiness becomes a radical act of care. Emptiness as digital detox, as mental space, as a design choice that renounces the superfluous to leave what truly matters: air, light, breath. It’s the square between buildings, not just an urban interstice but a place of encounter and sociality. It’s the clearing in a sacred forest which, in Shinto traditions, becomes a frame for the divine, a sacred space precisely because it is empty. It’s the Zen garden, offering nothing superfluous except its own essentiality, becoming a metaphor for contemplation and meditation.

To speak of emptiness as care means recognising we don’t need to fill every space to make it exist. On the contrary, emptiness is a reservoir of possibility, the field of all potential transformation. And above all, as Isabella tells us: “Emptiness is the last remaining luxury: a space you don’t need to justify, that exists to help you exist better.”

Chairs: a semi-serious anatomy of a design choice

Chairs are a strange kind of mirror. We sit on them for hours, we lean back, we grip their arms. Yet if we observe them closely, they reveal more than we think. They show us how we inhabit space, how we work, how we think. Bruno Munari once said, “Designing a chair means designing the body that will use it.” It wasn’t just a statement about industrial design, but an invitation to realise that every chair shapes the person sitting on it: it imposes postures, suggests durations, sets distances and degrees of intimacy.

We believe every gesture is an act of design, even choosing what to sit on. Observing chairs means reading our own cultural posture. That’s why we’ve created this small (semi-serious but methodical) map through design history and the psychology of inhabiting.

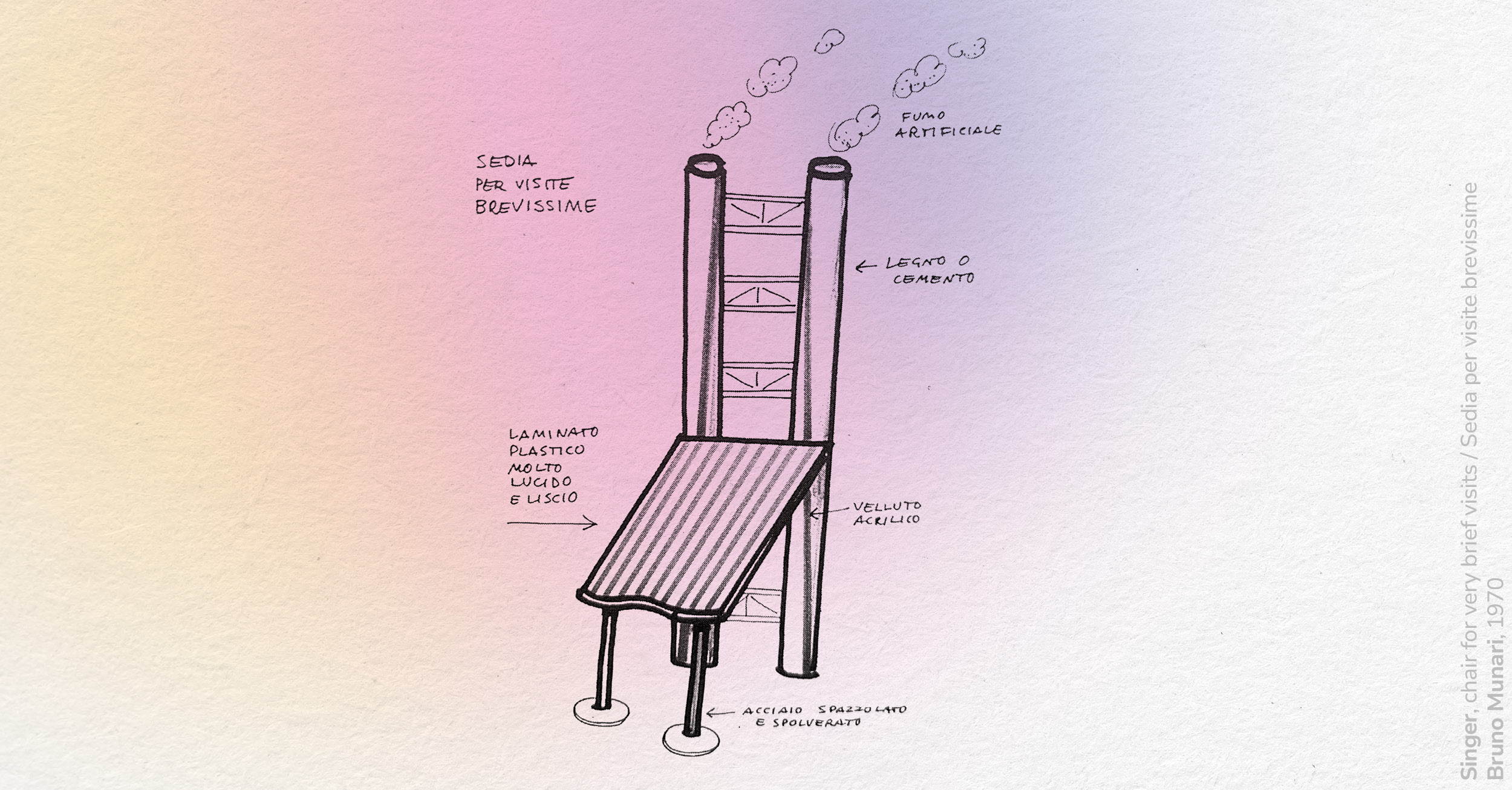

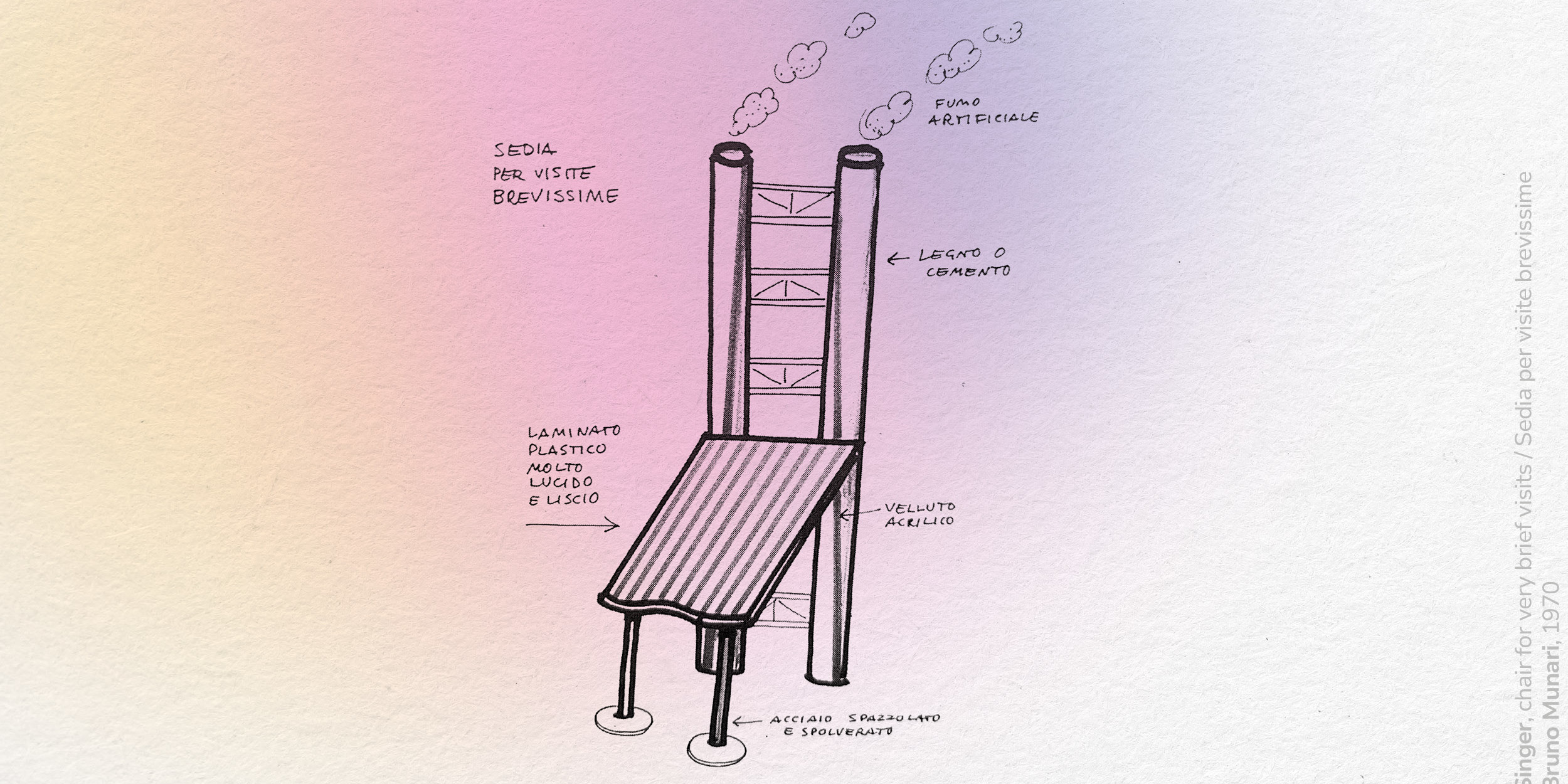

1. Bruno Munari’s “visite brevi o brevissime” chair

Munari designed it in 1945 as a conceptual provocation. An iron seat tilted forward, suspicious and slightly uncomfortable, intended for “very short visits”: the guest sits down but never relaxes, in fact, they slowly slide off. Needless to say, visits don’t last long. A design object can also be a psychological statement and social critique. This is the chair of someone who works with surgical efficiency: a minute longer would become an applied psychology session. If it could speak, it would say: “The exit is that way.”

2. Verner Panton’s Panton Chair

Designed in 1960 and mass-produced from 1967, it was the first chair made entirely from a single piece of moulded plastic. A pop icon of 1960s Danish design, it combined sculptural form with function, its S-shaped silhouette revolutionising the aesthetics of seating. This is the chair with the supple posture of someone who adapts to any change, but always with style. Today it sits in MoMA New York as a masterpiece of organic, industrial design. If it could speak, it would say: “I bend, but I don’t break.”

3. The Eames Lounge Chair by Charles and Ray Eames

Designed in 1956, it is the most iconic lounge chair in the world. Moulded wood, black leather, a posture that’s relaxed yet innately superior. Created to offer “the warmth and comfort of a well-worn baseball glove,” today it’s the throne of anyone who owns at least three volumes of critical theory and can quote Rem Koolhaas by heart – always with a gin and tonic within reach. If it could speak, it would say: “I’m working, even when I look like I’m on a break.”

4. The Aeron Chair by Herman Miller

Designed by Don Chadwick and Bill Stumpf in 1994, the Aeron Chair is the queen of contemporary ergonomics. Made of breathable mesh with no unnecessary padding, it offers infinite adjustments and has become a symbol of global smart working and tech office aesthetics. If it could speak, it would say: “My back comes first.”

Because chairs speak, too

Every chair is a personal manifesto: of power, comfort, or style. Observing it methodically, as we do with workspaces, means understanding who we are and who we want to be. In the end, that’s what design is about: interpreting details to create environments that truly reflect us. And this is where the Altis method comes in: analysing every choice, even the most seemingly banal, and transforming it into a conscious gesture aligned with how we live.

Emotions at Work: Not a Soft Skill

Emotions are everywhere. In involuntary gestures, in the tone of an email, in the glances exchanged during meetings. Yet when it comes to work, emotions remain confined to the realm of soft skills. Empathy, emotional intelligence, stress management. Beautiful words, all too often reduced to footnotes in a list of individual performance metrics.

But what if we were witnessing a shift, and what if the way we feel became an integral part of the way we work? This question doesn’t come from philosophy, but from cognitive psychology, neuroscience, and organisational anthropology. Fields that tell us, clearly, that emotion and cognition are one and the same: without the first, the second does not exist.

Emotional Based Working

At Altis, we call it EBW: Emotional Based Working. It isn’t a pre-packaged model, but an exploratory field we are mapping through our Proprietary Research. It arises from the evidence that no space, process, or company culture can truly work unless it considers the emotional dimension as a strategic resource.

Is it the opposite of ABW? No, it’s its complement. While Activity Based Working organises spaces and time around what we do, Emotional Based Working organises them around how we feel. Together, they describe work as it really is: a complex system of activities, relationships, emotional states, physical postures, and cultural narratives.

Why emotions really matter

Emotions are what allow us to make quick decisions, assess risks, create connections, and design with meaning. Neuroscientist Antonio Damasio wrote it decades ago: “We are not thinking machines that feel, we are feeling machines that think.”

Designing for emotions means creating spaces that are beautiful and functional, but above all able to activate emotional states coherent with the processes they support. It means recognising that a certain type of light, temperature, noise, or spatial arrangement can trigger irritation or creativity, fatigue or focus.

From activity to emotion: the next frontier

In our latest editorial exploration, we asked ourselves: is ABW still the best model? The answer emerged clearly: we don’t think it’s enough. On its own, it’s insufficient to grasp the complexity of contemporary work. To do so, we need to take a step forward – because it’s not only activities that define work, but also the emotions that drive, sustain, and transform them. And that is the true raw material of human work.