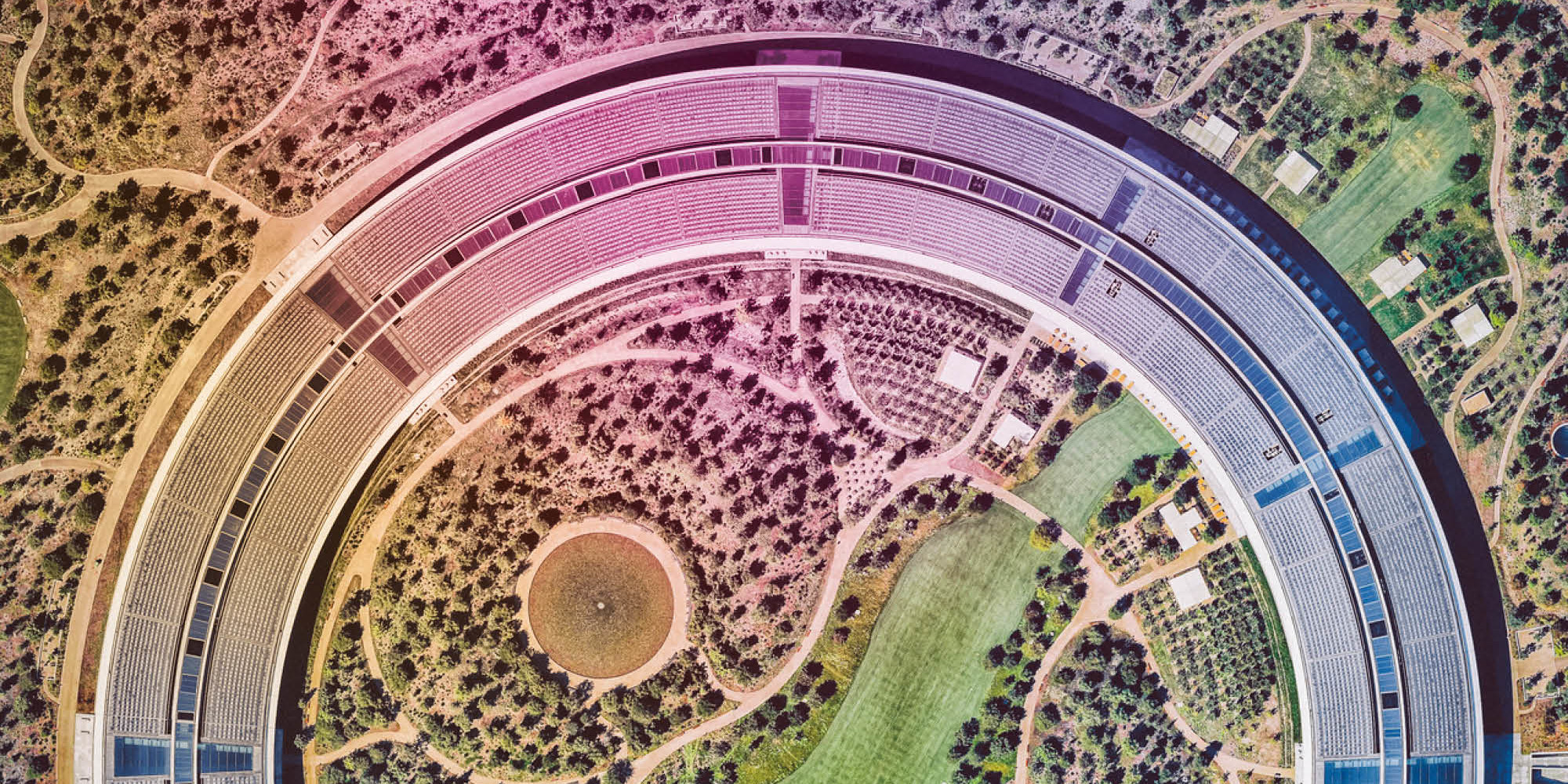

Everyone knows it, but few have truly experienced it. The Apple Campus in Cupertino is the secular cathedral of the 21st century: 260,000 square metres, a perfect ring designed by Norman Foster, curved glass panels everywhere – and a message that couldn’t be clearer: the future has already knocked here. But behind this geometric perfection that statically mimics an organic form, a question inevitably arises: is flawless architecture enough to reflect a work culture? Or, to put it another way: can a façade contain all the contradictions of those who work inside it? Probably not.

It’s not (just) about beauty

The Apple Campus is a monument to performance: vast open spaces, immaculate surfaces, diffused light. All designed to spark those “creative collisions” between employees that Steve Jobs held so dear – the same Steve who, back in the Pixar days, proposed a single central block of toilets to force people to bump into each other several times a day (a proposal eventually rejected by the execs). That principle lives on in the ring shape of Apple Park, pushed to the extreme. But did you know that when the campus first opened, many teams actually asked to stay in their old offices? Or that Apple, post-pandemic, was among the strictest in enforcing the return to office, stirring internal controversy? That’s where the narrative starts to crack. Because when the shell is louder than the experience, architecture becomes representation – and nothing more.

Caution: Beyond Form, We Need Coherence

For a space to truly work, it doesn’t just need to be beautiful – it needs to be authentic. A headquarters sends a message, but if the people inside don’t feel it belongs to them, that message loses its meaning. And this isn’t just about Apple – the issue is systemic: it’s the myth that the environment can replace culture, that all it takes is “designing” a way of working to make it effective. The point isn’t to abandon ambition or aesthetics. On the contrary: they should serve the real, everyday experience of people. Because if architecture doesn’t engage in dialogue with those who live and breathe the space, it remains a surface. And today, more than ever, we need less façade and more depth. Less object worship, more design ethics. Icons can teach us a lot – absolutely. But icons aren’t there to be copied. They’re there to be interpreted. To create a beautiful office, you need an architect. To create an office that works, you also need a method.

That’s why we like icons: they make excellent starting points for healthy debate. If you’d like to talk about it, drop us a line at [email protected].